Belonging to the best

Which factors lead companies or corporations being among the best-performing worldwide?

To answer this question, McKinsey consultants Bradley, Hirt and Smit surveyed around 2,400 global companies to determine how much economic profit they generated over a 15-year period. This key figure indicates, in somewhat simplified terms, whether the company generated a market-driven interest rate on the equity employed after deducting interest on debt and taxes, and thus increased the company’s value from the owner/shareholder’s perspective (see also the post “Profit in Line with the Market”).

The following comprehensive graphic stems from the book “Strategy Beyond the Hockey Stick” (Chris Bradley, Martin Hirt, Sven Smit, 2018, p. 43).

This international analysis showed that 20%, or around 480 of the companies analyzed, realized a higher than market-driven return, 20% realized a lower return and 60% (1,440 of the companies) did not achieve any significant increase in corporate value.

In addition, the authors evaluated that within 10 years, of the 1,440 companies considered in quintiles 2–4, 210 companies “slid down” into quintile 5 and 120 made the leap into the top quintile.

Thus, only 8% of the “middle-class performers” managed to move up into the top class, while 14% were relegated to quintile V, in which corporate value was “destroyed”, i.e. from a shareholder perspective, only an insufficient return on risk capital was achieved (chart ibid., p. 78).

Since these findings emerged from a global analysis of the real economic development of thousands of companies, the three authors refer to this evaluation as the Power Curve of Economic Profit. One can also speak of a “power law”.

Based on this enormous database of company performance over 15 years in 127 industries and 62 countries, the authors analyzed 40 variables of business success. They found that 10 of these variables, or levers, are the key metrics for predicting business performance over 10 years (p. 99 ff.). These key metrics are:

Sales, debt, research, industry trends, geographic trends, acquisitions, resource allocation, investments, productivity, differentiation (translation and explanations by the author of this post).

Key figures 4 and 5 are externally determined factors, while key figures 2, 3 and 6-9 are the result of management decisions at the group management level and their practical implementation. Sales development (1) and growth rates compared to the competition (10) are the consequences of implementation.

Explanation:

If a company achieves a market-driven interest rate, i.e. is profitable, but hardly manages to increase its shareholders’ equity and thus the company value, it becomes “boring” for shareholders and potential investors. The company moves in quintiles II – IV and runs the risk of slipping into quintile V if sales collapse.

Such developments deter potential investors from providing the company with additional equity. As a result, the company has fewer opportunities to increase sales and achieve higher market shares. If one or more of these ten key figures develop negatively, these are warning signals.

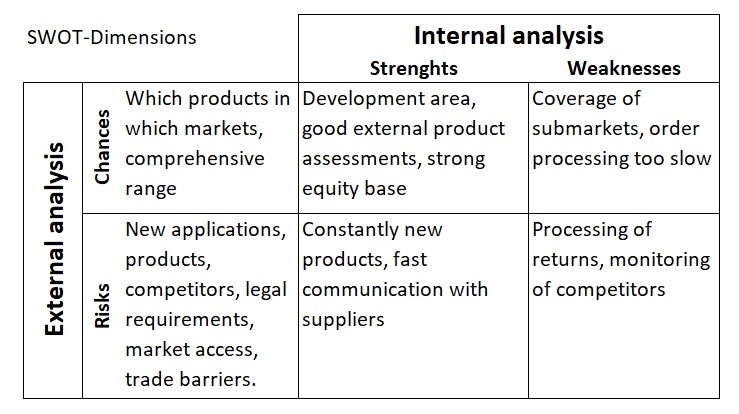

These warning signals are significant, but come a little late. The important early warning signals arise in the four corporate environments. These are technological, market-related, social or economic developments that indicate impending changes, as well as developments in the natural environment (see the post “Environmental Changes are Crucial”).

Based on the key findings of the McKinsey analysis and the derived power curve (power law), it is possible to make the search process for weak signals more accurate. 10 questions to ask (key figures affected from above in italics in brackets):

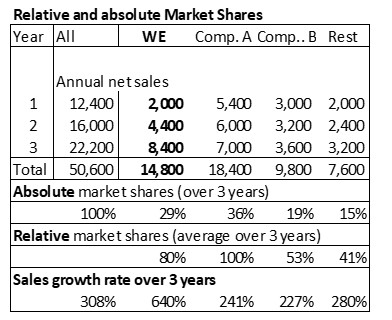

A Which companies achieve faster sales growth than we do in our served markets and why? (external, 1.4)

B Which product group sales grow faster in the industry than they do for us? (external, 1.10)

C How are the net revenues of our product groups developing in different economic areas or countries? (internal, 1.10)

D Our competitors have acquired other companies. What could this mean for the development of our markets? (external, 4.5)

E Is the consumer spending (end consumer) shifting to other product or service areas and, if so, in which customer markets? (external, 4.5)

F Do new raw materials or processing methods enable more cost-effective production? (external, 3,4,6,9)

G Which technological developments could lead us to adjust our strategic intentions or even our corporate purpose? (external, 6,7,8)

H Is it appropriate to adjust our current resource allocation based on expected environmental developments? (internal, external, 7)

I Which social developments have the potential to change the weighting of consumer spending? (external, 4,5,7)

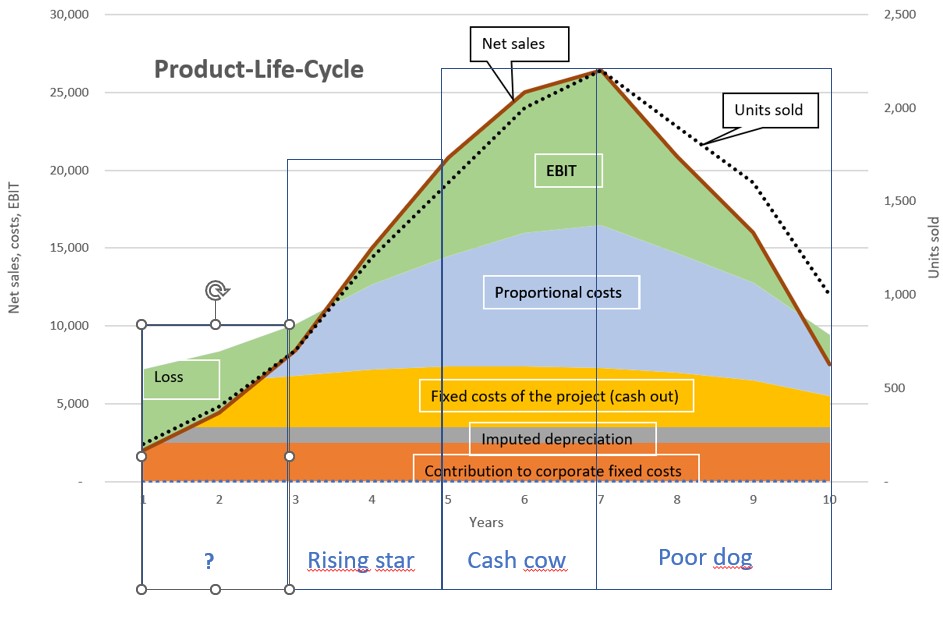

J Are proportional costs growing slower than our net revenues, and are fixed costs growing more slowly than billed revenues? (internal, 7,8,9)

Companies that are successful in the long term (Quintile 1) continuously monitor developments in the various spheres of their organization and adapt to developments as necessary. This is not a new insight, but it is essential for survival (see the example of IBM in the article “Weak Signals”). The purpose of linking the success-determining factors from the McKinsey analysis with developments in global markets is to ensure the continued existence of the company. The sample questions A-J show the need to recognize developments that can be expected outside the company and to include them in your own planning.

Who should prepare and comment on these analyses and when, and who should make the necessary planning decisions is the topic of the next post.