The present value of a strategy

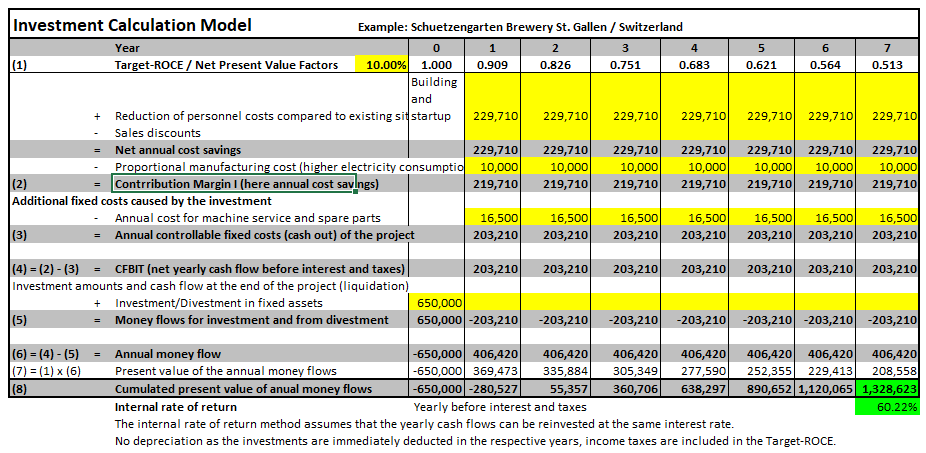

Dynamic investment appraisal is the most suitable tool for assessing the financial impact of the strategy implementation project. This is because it includes the entire time horizon of the strategy and takes into account not only the expected net revenue, costs and investments in the respective year of origin, but also the development of the balance sheet items.

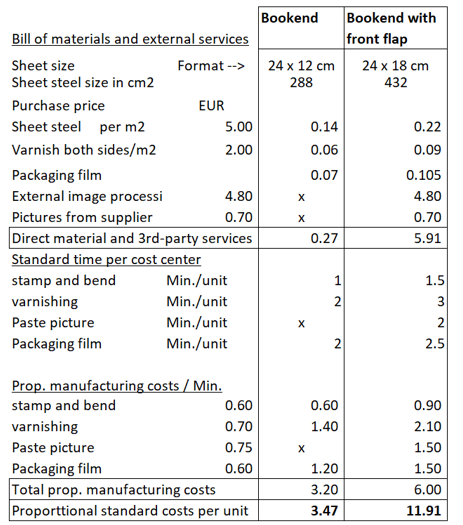

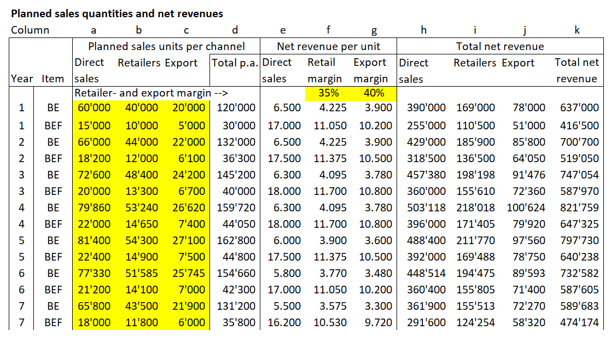

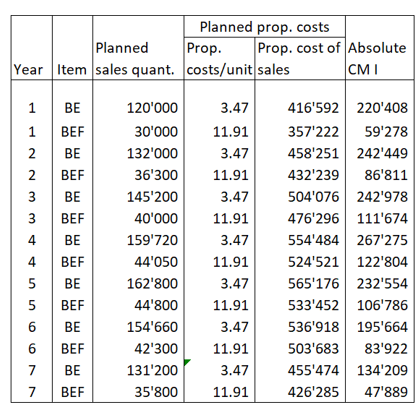

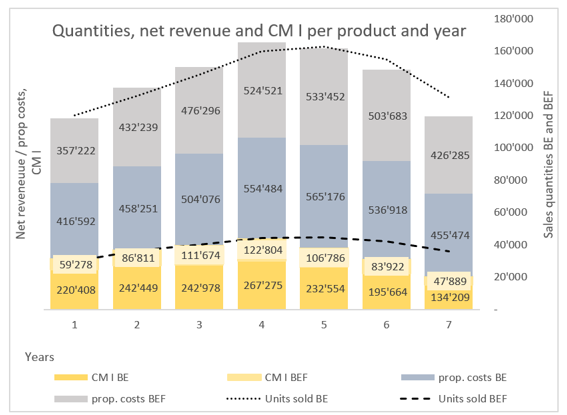

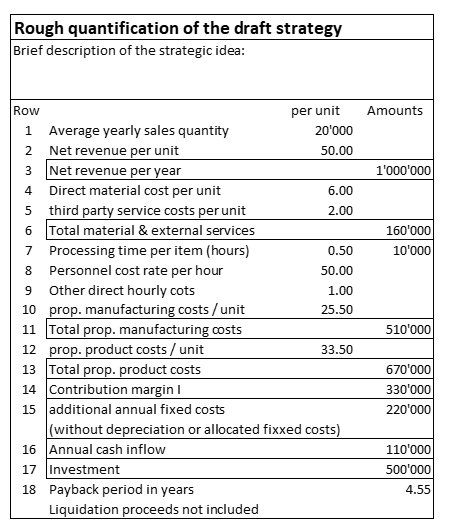

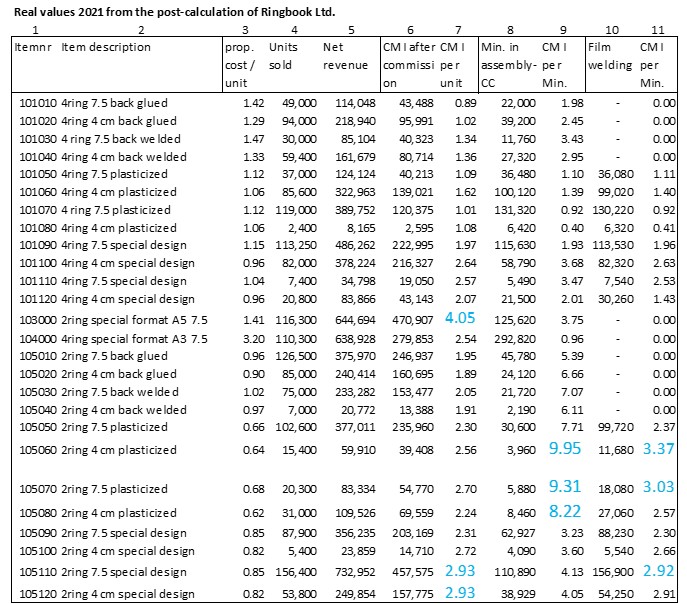

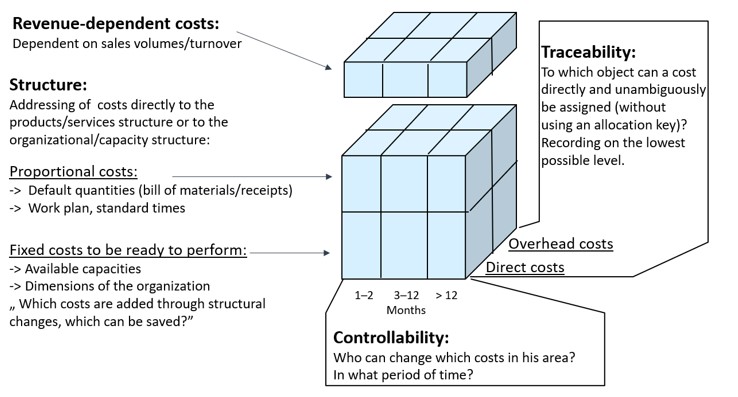

From the contribution margin calculation in the post “Precalculation of a Strategy Implementation“, the unit-dependent CM I are transferred to the investment calculation for each year. They represent the expected annual cash inflows from the market (rows 1 – 8).

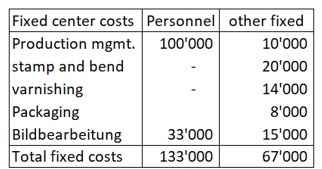

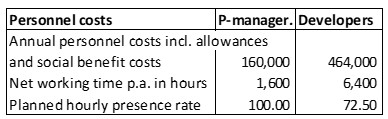

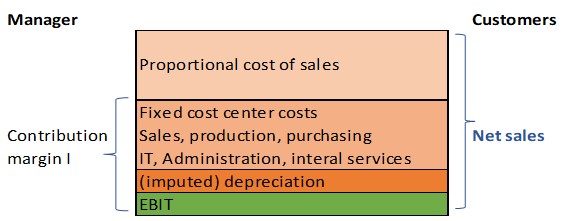

The expected cash outflows for additional fixed costs are deducted from this (rows 10 to 12) in accordance with the information in the post “Quantifying the implementation project”. This leaves the cash flow before interest and taxes (CFBIT, row 13) for each plan year. This cash flow is first used to pay for the net investments in the company’s balance sheet. The remainder belongs to earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT).

Change in balance sheet items

A strategy has an impact on various balance sheet items:

-

- Sales growth automatically leads to an increase in accounts receivable. If customers pay their invoices usually after 30 days, 1/12 of the turnover is not yet in the bank account and is not yet available for the payment of wages and purchases (calculation in row 14).

- Sufficient inventory of finished standard bookends BE is always required to ensure timely delivery to customers. The company should always have the estimated bookend requirement for 30 days available in stock. If sales increase, the assets tied up in the finished goods warehouse must therefore also increase (rows 15 and 16). The front flap bookends BEF are only produced to order. They therefore have no stock.

- The semi-finished and finished goods inventories are only valued at proportional production costs. This is because the cost center fixed costs are included in rows 10 + 11, see the post “Flexible Budget“.

- To be able to produce on time, the necessary stocks of raw materials and semi-finished products also increase. These also tie up assets but are neglected in this example.

- Similarly, increasing purchases lead to higher accounts payable. If suppliers are paid within 30 days, a purchase will also only debit the bank account 30 days later (row 17, but not filled in the example).

- If a strategy requires investments in fixed assets, their payment reduces the bank account balance or increases the bank debt. The investments required for strategy realization were listed in the post “Quantify implementation project” and are shown in row 18 in the planned year of the investment.

All cash flows from operations (rows 1 – 13) and from investments and divestments (rows 14 – 20) are summarized in row 21. This shows the absolute cash inflows and outflows the strategy should generate during its lifetime. Cash outflows are expected in years 0 (start of strategy implementation), 6 and 7. In the other years, there should be positive cash inflows.

Is profitability in line with the market?

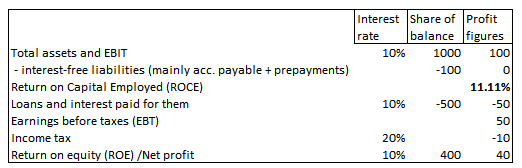

When private individuals or companies lend money to others, they usually expect to get this amount back and that they will also receive interest on the money lent. This automatically raises the question of which interest rate properly covers the risk of the loan.

Because quantifying the risks of money lending is a global concern, statistical analyses are carried out annually to determine the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) for various industries in many countries. We summarized these analyses with data from 2013 in the book 360° Management on pages 243 ff. and evaluated them on a country- and industry-specific basis. For an “average company” in Germany, this resulted in a target ROCE (return on capital employed) of 10%, for Austria of 9.5% and for Switzerland a target ROCE of 6.5%. In 2023, the percentages were roughly the same. The difference between Germany/Austria and Switzerland is mainly due to the fact that the market risk premium and the current profit tax rate are significantly lower in Switzerland.

If a WACC of 10% is assumed for Bookends Ltd., this means that the expected cash flows from the strategy project must be discounted to the decision date (end of year 0):

Notes:

-

- The present value-factor of the cash outflows in year 0 is 1.0 because the cash outflow happens at the beginning of the strategy implementation (present value factor = 1).

- The cash outflow of 81,120 at the end of year 1 has a present value of 73,827 at the time of the decision for the strategy (present value factor = 0.909). This is because the money will not arrive until one year later after starting the strategy realization. If this present value is subtracted from the 150,000 initial investment, the present value balance of the strategy at the end of year 1 is -76,173.

- The cash flows of the following years are also discounted at an interest rate of 10% and accumulated in row 23.

- At the beginning of year 4, the cumulative present value balance is > 0 (line 22). This means that the previous investment amounts have been fully repaid as well as the interest of 10%.

- The net revenues and the contribution margins decrease from year 5 onwards. The life curve of the front flap bookends is slowly coming to an end. Nevertheless, positive cash flows are still realized up to year 5. This is in line with the experience of many companies that the cash flows from the products in the cash cow and poor dog phase are used to earn the money to finance the question marks (see the post “Evaluating the product life cycle”).

- In years 6 and 7, the cumulative cash value decreases again and develops negatively. As shows line 9 in the complete investment calculation, considerable CM I can still be generated. Consequently, in year 5 it will be necessary to consider how the fixed costs of the strategy (rows 10 and 11) can be reduced in good time, e.g. by employing the bookend staff in cost centers that will then have uncovered personnel requirements.

- The Excel function “IRR” can be used to calculate the internal rate of return of the annual cash flows of the strategy (17.7%). This rate is important if several strategic ideas are competing for available investment funds.

Conclusion on strategy quantification:

It is advisable to quantify strategic projects already at the planning stage and therefore before the final decision is made. To this end, achievable additional net revenue, expected proportional production costs and changes in fixed costs should be taken into account. Stepwise contribution margin planning in combination with the present value calculation provides these insights before the budgets are released.