Weak Signals

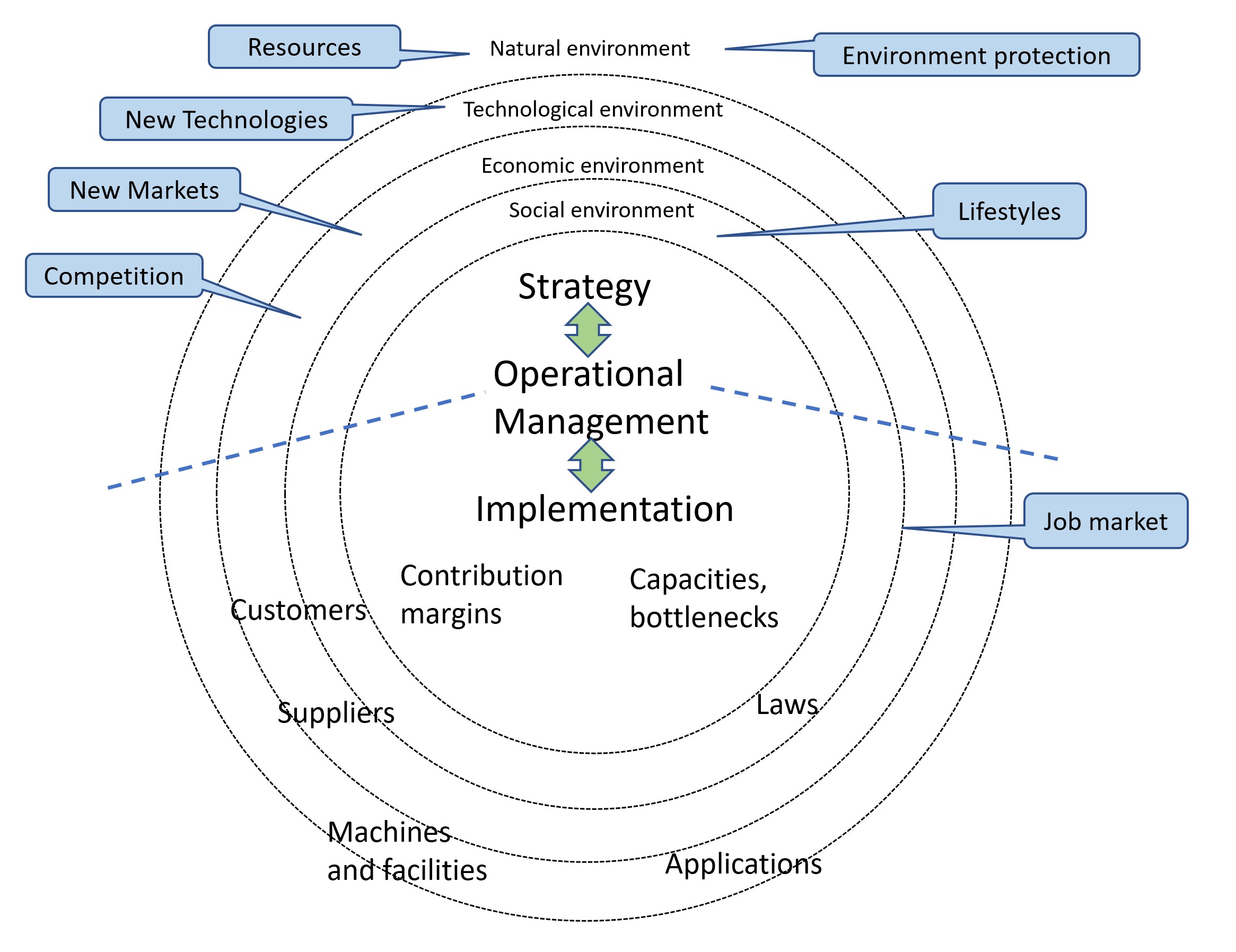

The media report daily on new developments in the various sub-environments of a company. News about new technological findings, newly offered products or services, shifts in market demand, new competitors, new technical and legal regulations and changing consumer behavior could have an impact on future business and jobs. The diversity of such news is overwhelming.

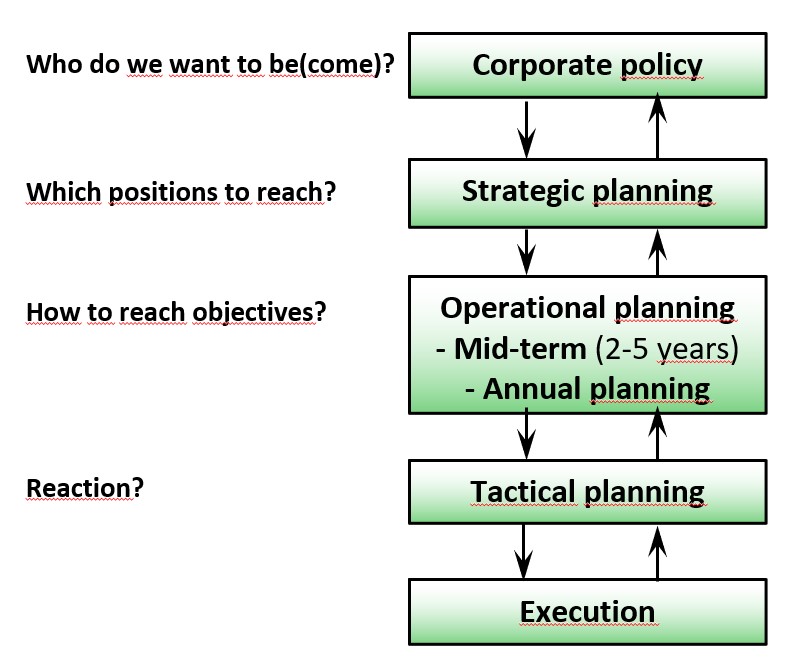

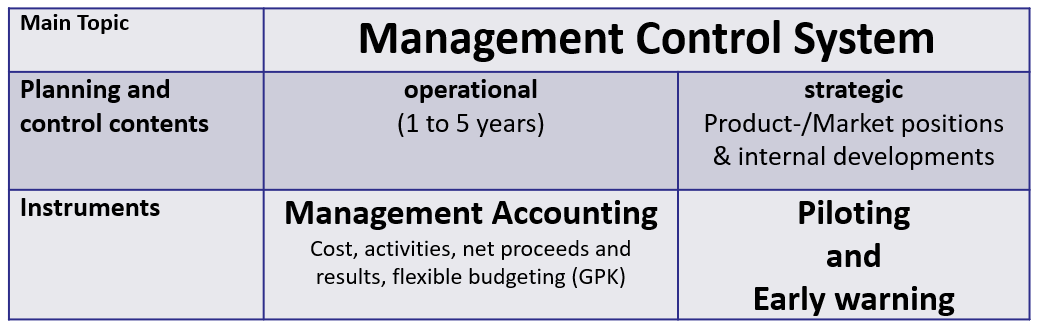

Managers are wondering how they can achieve the goals of their operational business and at the same time not miss any developments in their corporate environments that could affect their business model in the future.

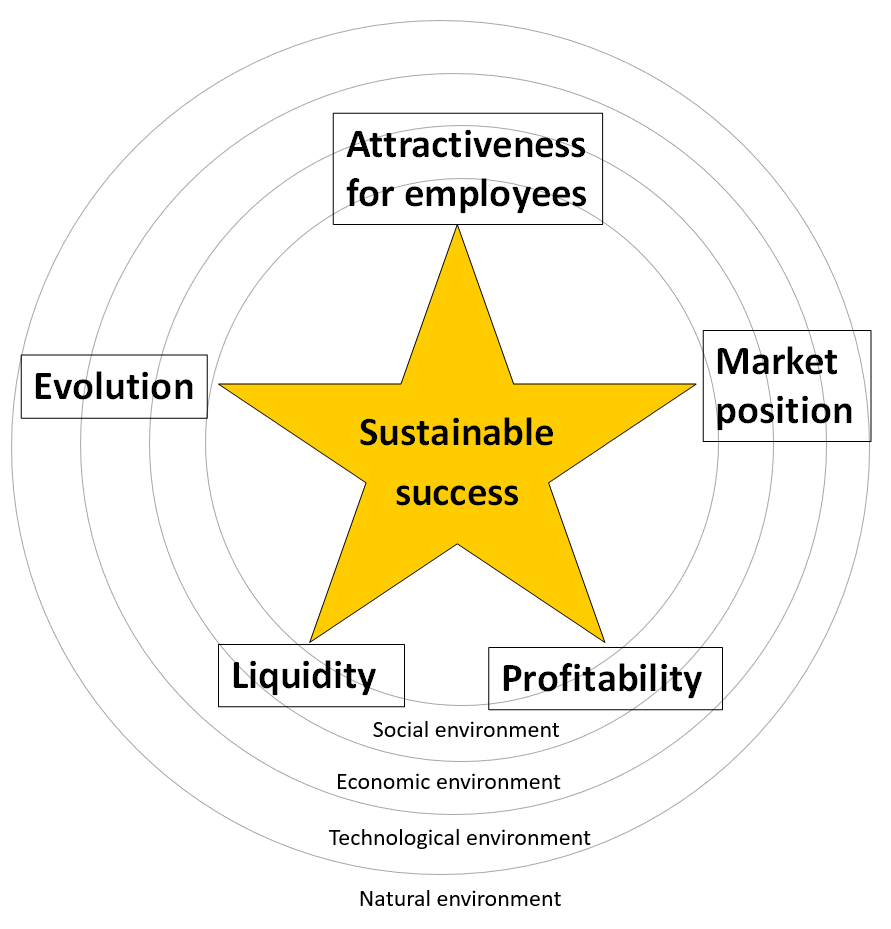

“The basic engine of data-, quantity– and value flows” shows that the achievement of objectives can be achieved within the company system, but that information on the future positioning of the company can only be found in the company’s sub-environments. The right external orientation is essential for the company’s survival. However, no organization has the capacity to evaluate all external messages with a suspected connection to its own future. The idea of searching for weak signals in the corporate environments can help.

Weak signals are generally referred to as the “… earliest, smallest signals that indicate possible changes, but whose effects are not yet fully recognizable” (free translation from P. Gomez, M. Lambertz, Leading by Weak Signals, p. 9). A weak signal should be followed up if its content could become important for the implementation of one’s own strategies or for the continued existence of one’s own company.

Employees, managers and company owners hardly have time to cope with this flood of data, as they are already fully occupied with operational management. Therefore, it is important to consider:

-

- What makes a message a weak signal?

- How can weak signals be filtered for one’s own organization?

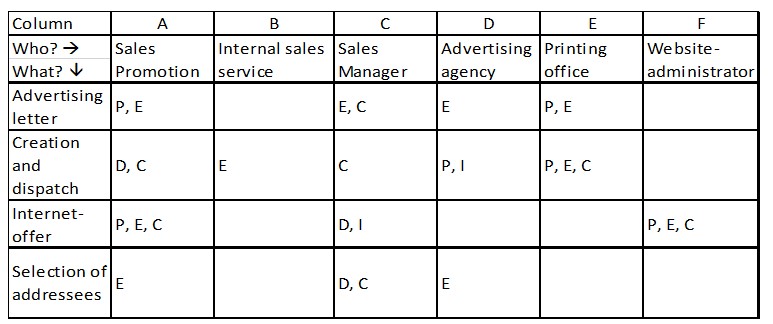

- Who is responsible for evaluating and processing the data and deciding what needs to be assessed internally (triage)?

- How are one’s own specialists and managers involved in assessing the weak signals in relation to the company?

- Who decides whether the insights gained require strategic and operational plans or even corporate policy principles to be adjusted?

Regarding 1 and 2: The signal should relate to the needs of the company’s own or prospective customers, to the company’s range of products or services, or even to the company’s basic ability to survive. Newly offered services or products could make the company’s own offering obsolete or at least compete with it. The know-how of the company’s own employees could no longer be sufficient to meet the changing demand. The possibilities of procuring raw materials and services for the manufacture of one’s own products and services could be restricted or the purchase prices could rise dramatically. Legal regulations or political developments could impede or prevent the sale of one’s own products. Finally, behavioral changes in in the social environment can also be weak signals, for example, when leisure time is given more weight than disposable income.

3 and 4: Those who are mainly involved in production, distribution and customer care have little time to worry about potential changes in the business environment. Personnel capacities must be built up to monitor environmental changes and classify their potential effects (in-house and/or external agents). They should explain the weak signals identified to the planners, preferably before the strategic planning is revised, so that they can incorporate them into their planning considerations.

Ad. 5: The assessment of weak signals leads to a need for action and thus to more working time and additional expenditure. The resources required for this (especially personnel and money) must be approved by the company management and the owners, since the downstream areas do not want to and cannot take responsibility for this.

To ensure the successful continued existence of a company, management must decide whether the strategic and operational plans are to be adjusted based on “weak signals” or whether the purpose of the company should be changed.

Sustainable success, early warning and weak signals

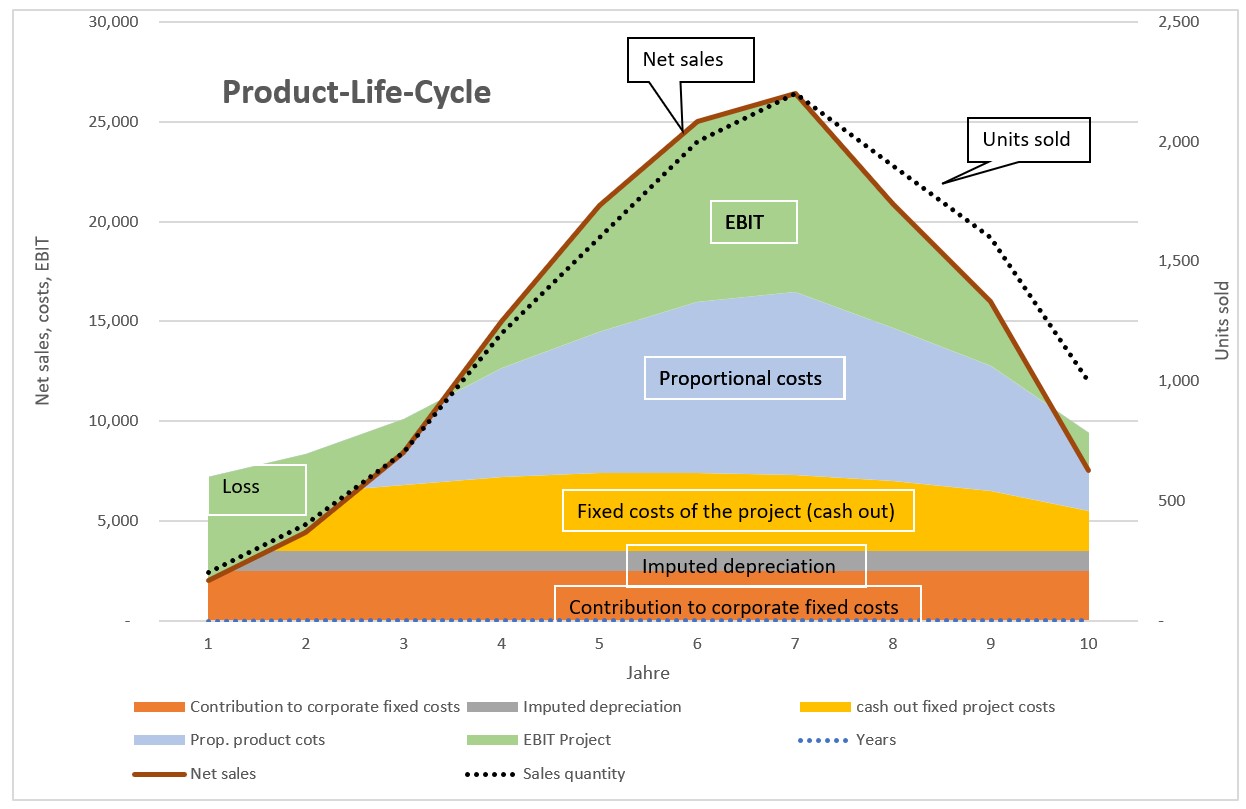

Companies with a future should be resilient. They must be able to cope with stress and crises as well as new challenges in order to develop in a healthy way. This is achieved when the company adapts its offerig to the future requirements of the market in good time, because markets and thus demand are constantly changing. The products and services that are successfully sold today lose their market position because other companies bring new, more promising offers to the market for potential customers. As a result, the company’s own sales and contribution margins fall, profits melt away and the staff that was previously relevant for success seeks better jobs.

Weak signals in the corporate environment should lead to the identification of impending changes before they occur. This is because the organization needs time to adapt to impending changes.

Weak signals, especially from technology, sales and procurement markets, as well as from the social environment, provide indications of which developments are to be monitored in the near future. To avoid the capture and analysis of weak signals getting out of hand and leading to paralysis through analysis, the search area must be narrowed down.

Since its foundation in 1911, IBM Corporation has continuously observed weak signals, developed new products and applications for them, and has revolutionized the way it approaches the market on numerous occasions. Details can be found in Wikipedia .

At the beginning of the 1980s, the author of this article was still learning how to punch cards, to program the forerunners of spreadsheets and to sell the available systems. Since then, IBM has completely reinvented itself at least four times. Midrange computers, personal computers, printers and other peripherals are business areas that IBM sold years ago when they were still generating considerable profits. Today (2024), IBM is at the forefront of cloud computing, blockchain technology and data security, artificial intelligence and consulting. The share price was around $14 in 1994 and $170 at the end of 2023.

From a helicopter perspective, it appears that IBM has continuously moved from one product or market life cycle to the next. When the growth curve was still pointing upward but the growth rates began to decline, they began to conquer new markets with new technologies. In order to raise the cash needed to develop the new business areas, they sold off financially (still) successful parts of the company so that they could invest the liquidity in new business areas.

Empirical studies by McKinsey consultants Bradley, Hirt and Smit prove that the approach of lining up life cycles, as described, is an effective idea for achieving sustainable growth. Peter Gomez and Mark Lambertz show how the search for suitable weak signals for one’s own company can be focused by analyzing leading indicators.