Determine the deciding purchase-criteria

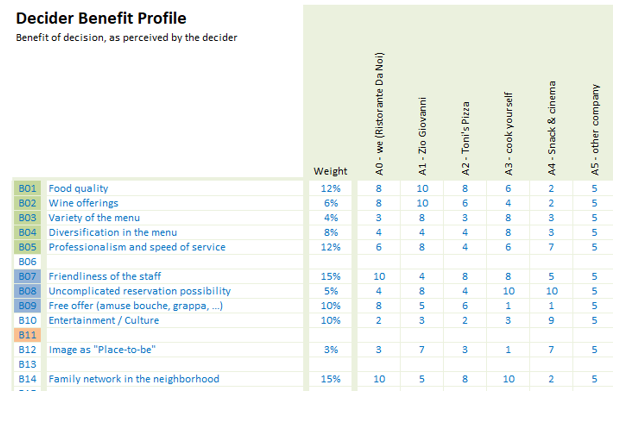

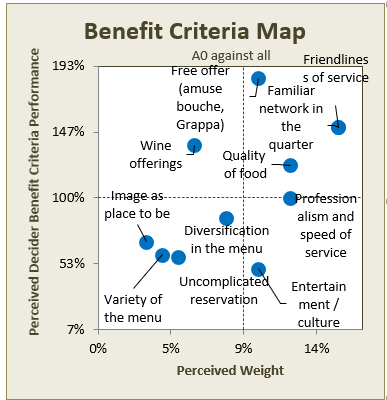

The complete perceived benefit is determined on the basis of weighted benefit criteria. Not only the criteria that constitute the product or service are taken into account, but also service, added value and image elements. If it is a classic, haptic product, the constituent criteria are usually equivalent to the technical data: Engine performance, load volume, cycle frequency, compactness of dimensions, manufacturing tolerance or similar.

If the customer benefit analysis is created for a service, it is about the criteria that constitute this service. In the case of a logistics service, for example, these are the prompt delivery of the goods, in the case of a consulting service the technical competence of the consultants, or in the case of a training service the probability of passing the diploma examination.

Both in the purchase of haptic products and in the purchase of services, non-constituent, complementary services can play a decisive role. In the jargon of customer benefit analysis, one usually speaks of service criteria. Depending on the business, these include the professional quality of sales advice, delivery times, friendliness of service, warranty services, density of the network of service points, availability of spare parts, uncomplicated booking of an upgrade, availability of a hotline, etc.

Added-value criteria provide added value from the customer’s point of view, e.g., “recyclability” or “made in the United States”.

Image criteria evaluate the brand image or the image of influencers promoting the product. In business-to-business transactions, (project) references are often important, especially in new customer business. In existing customer business, on the other hand, the image criterion “worked great last time” can play a central role. It stands for a presumption of competence, on the basis of which the existing customer proceeds to purchase without further factual examination of all other criteria. Especially in a project business, it is often underestimated how important the project staff of today’s project are – they are the most important “salespeople” for the next project.

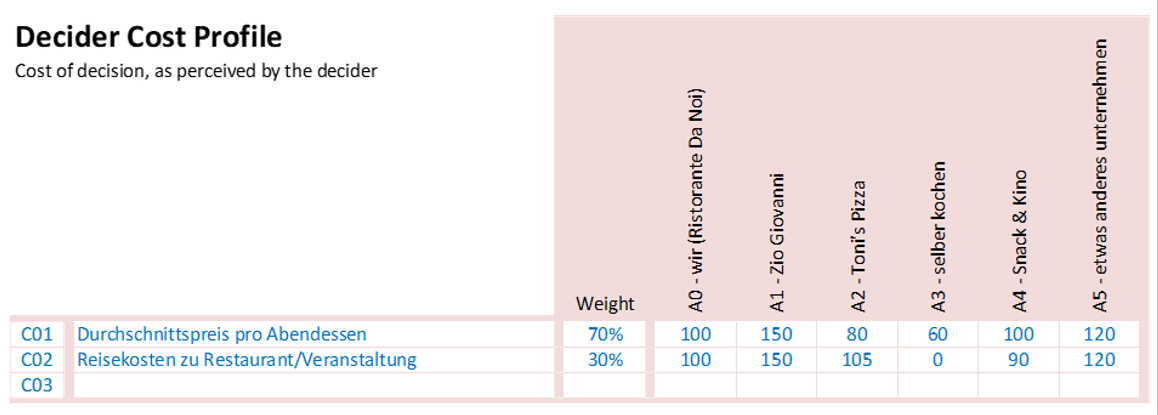

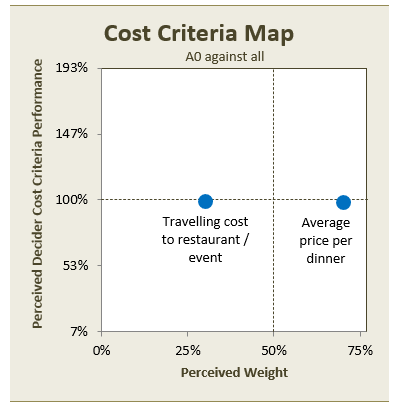

Analogous to the benefit, the total costs perceived by the potential customers are determined with weighted cost criteria. These typically include one-time and recurring monetary costs. One-time monetary costs include the sales price, but also one-time project investments (financial experts speak of Capital Expenditure, or CAPEX for short). Recurring monetary costs include maintenance costs, license costs, consumables, etc. (the financial experts speak of Operational Expenditure, or OPEX for short).

Although both CAPEX and OPEX are monetary values which the financial calculator can condense into a Net Present Value (NPV), it is advisable in the customer benefit analysis to clearly distinguish between these cost criteria. In the purchase decision, the calculation is usually not 100% financial, but political factors also play a role. Some customers do not like CAPEX and therefore weight the one-time monetary cost criteria higher than the recurring ones. Others do it the other way.

The non-monetary cost criteria also play a significant role in the purchasing decision. These include, for example, the time required on the customer side to purchase and operate a product. Other non-monetary costs that can play a role in the purchasing decision include the personnel capacity absorbed on the customer side, the space required, or the dilution of management attention.

Non-monetary costs can also include opportunity costs – i.e., the regret that by deciding to make a purchase, one forgoes the opportunity to buy something else, because there is no more budget available. Sunk costs, i.e., expenses from previous decisions, can also play a deciding role. If a buyer decides to buy a new IT platform, the investments already made in the old platform become obsolete. Controllers know that sunk costs have no place in decisions to invest in the future. Nevertheless, many customers take earlier expenses into account for political or emotional reasons. If product development and/or marketing do not take this aspect into account, their communication could miss the customer’s needs.

Cost criteria also include all kinds of risks that the customer associates with the purchase decision and which he wants to minimize. These include capital loss, currency, liability, or reputational risks.

In the customer benefit analysis it is essential to analyze a decision from the customer’s perspective. Even if the host is a wine lover, it does not mean that customers come to the restaurant because of the quality of the wine list. Perhaps the friendliness of the service is much more important to them – a benefit criterion that the host perhaps weights too low or overlooks altogether. Whether the service is friendly and courteous is judged (and told) by the customers, not the host.

Often it is not clear at first whether a criterion is more of a cost or a benefit criterion. Taking the customer’s point of view without compromise leads to the solution here as well. For the tightly calculating businessman, the gasoline consumption of a vehicle is a clear cost criterion. For the urban hipster who wants to brag about hi-tech to his colleagues, the (very low) fuel consumption is more of an image criterion on the benefit side.

Self-image versus external image

When conducting a customer benefit analysis, it is common to first create a so-called “self-image”. In doing so, managers record how they believe their customers “tick”. In most cases this results in quite robust images. These self-images should be validated with external images in a timely manner. Personal interviews, surveys or focus groups are recommended for this purpose.

Ideally, the self-image is created in a heterogeneous team in which the sales, management and technical perspectives are combined. The self-image created can then be checked for plausibility in a closer environment, e.g., with work colleagues outside the work group. In the next step, customers who have already been approached are consulted.

These steps involve the validation of the alternatives considered by the customer as well as the cost and benefit criteria. The weighting of the criteria shares and the comparative evaluation of the alternatives can be collected by means of web-based surveys.

At each stage, including large-scale surveys, it is important to allow open responses. Good, step-by-step preparation can prevent a large-scale survey from revealing that “the market” has been completely misunderstood. If this is the case, however, one should start again from the beginning. Otherwise the risk is to invest in a different business than the one in which the (potential) customers are looking for the best cost/benefit ratio.