Managing inflation internally

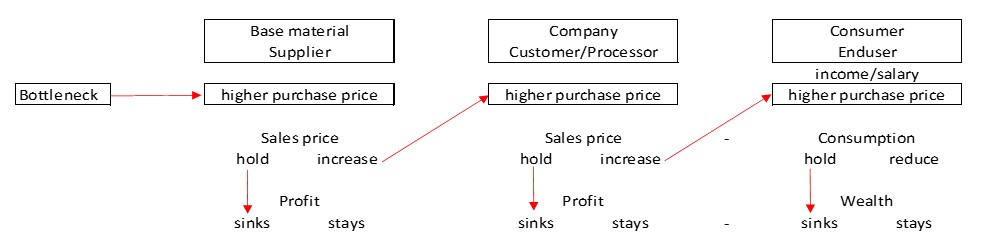

A company can rarely pass on supplier price increases in full to its customers. Managing inflation internally is a must. This is because the company’s existing customers will, in their own interest, try to buy cheaper from other suppliers, consume less, use other input materials or even withdraw their own offerings from the market, because they are no longer profitable due to price increases. Potential new customers will also compare offered prices and services and order where they feel they get the most for their money.

A bidding company must therefore maintain its own profitability despite inflation so that it can continue to invest in its own future. Professor Simon calls this profit defense (p. 56 in the book Beating Inflation). In terms of planning and control, profit “should be included in the calculation from the outset like a cost variable to be covered (ibid., p. 52).” This requires the continuous increase of effectiveness and efficiency of one’s own actions. (Definitions in the glossary)

Effectivity = doing the right things

Efficiency = doing the right things right.

Therefore, all cost centers must find, decide on and implement measures that are suitable for achieving profitability in line with the market (see “Profit in Line with the Market “).

Cost reduction measures for functional areas

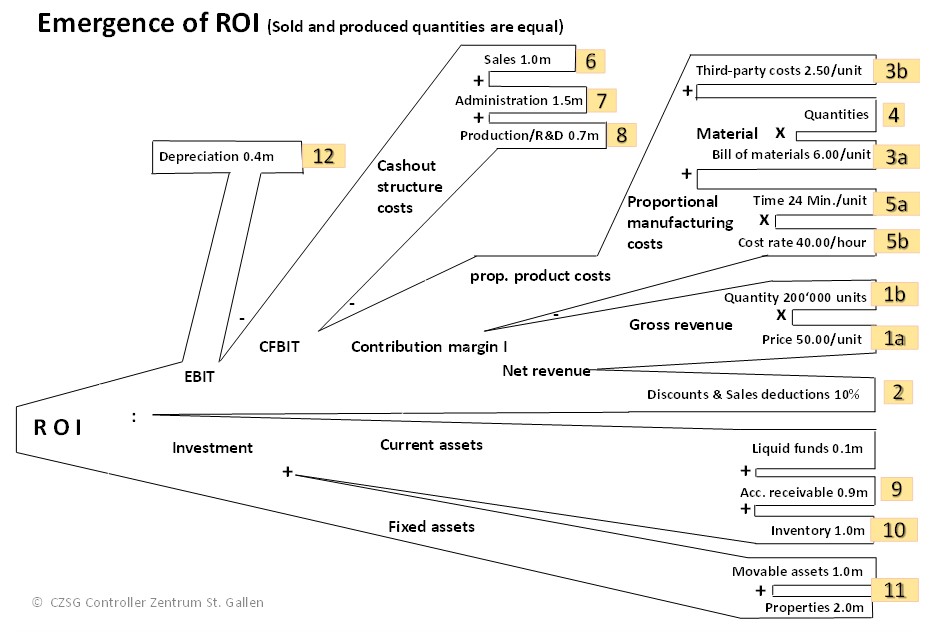

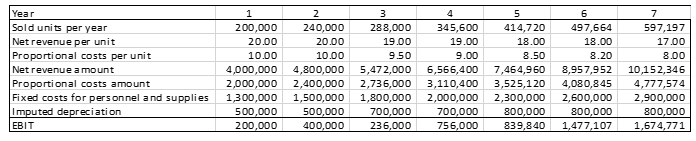

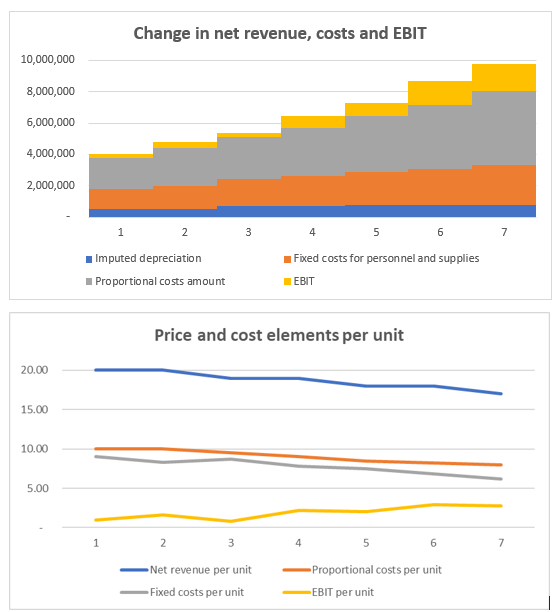

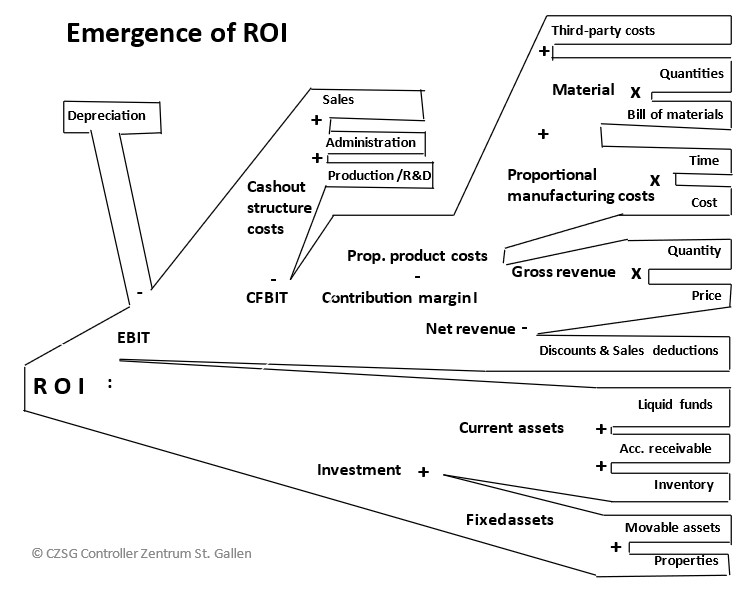

The ROI-tree from the post “ROI and Inflation” helps to generate ideas to increase profits, to evaluate these ideas from a financial point of view and finally to measure their implementation success. Exemplary starting points are structured below according to functional areas:

Sales, prices, conditions:

-

- Announce and justify price increases quickly, even if customers temporarily switch to competitors (get ahead of the “cost wave” with price adjustments).

- Increase prices in several steps to discourage customers from switching.

- Do not give discounts at the time of ordering but pay refunds when a predetermined purchase volume is reached (sales model).

- Fix terms of payment without cash discounts and accelerate the dunning process in parallel (cash discounts directly reduce profits).

- Develop new pricing models, e.g. pay per use or pay per period (applies especially to products or services with low proportional manufacturing costs).

- If the product or service is superior to competing offers, customers will buy at even higher prices.

Marketing, sales, distribution:

-

- Care for existing customers according to ABC-analysis (A and B customers generate higher absolute contributions and should consequently be looked after more intensively).

- Continuous procurement of new leads (addresses of potential new customers) and prompt contacting.

- Largely digital customer engagement to reduce customer visits (less travel).

- Analysis of contribution margin development after trade shows and exhibitions.

- Fix advertising contributions to reselling customers as a share of your contribution margin and grant them only after the sales have been achieved.

- Free delivery of a part of the order quantity often reduces the customer contribution margin less than direct discount percentages from the sales price, because only the proportional costs reduce the contribution margin.

- Continuous monitoring of competitors’ prices, assortments and sales development to locate opportunities for new offers.

- Completely automated dunning system to reduce days sales outstanding.

Manufacturing processes / production planning and control:

-

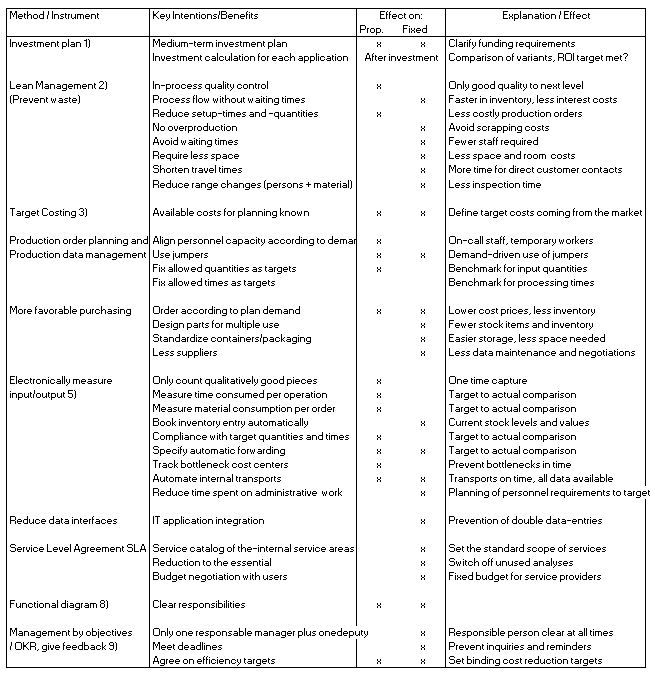

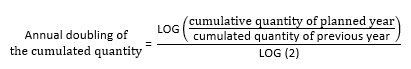

- Larger production batches reduce proportional manufacturing costs per unit, as setup times are incurred only once per batch. It is worthwhile to regularly reconcile order intake with inventory levels and the size of production orders.

- Train employees to master several processes and thus have less idle time.

- Automate process steps. In times of inflation, it is often easier to obtain funds for investment, albeit at higher interest rates.

- Continuously check whether suppliers offer certain semi-finished products cheaper than you can produce them yourself (in- or outsourcing based on proportional manufacturing costs plus direct fixed costs of your own process).

- Introduce computer-controlled processing steps and thus reduce manpower requirements.

- Digitalization of planning and control of production orders as well as production data acquisition.

- Reduce scrap.

Purchasing and inventory:

-

- Consumption scheduling per purchased item based on planned consumption of production and sales in order to achieve more favorable framework-agreements with suppliers.

- Regular comparisons of purchase prices of potential suppliers. Have a substitute supplier ready for each procurement item.

- Immediate information of the sales department and other affected cost centers in case of imminent price changes of important articles or services to be procured.

- Report purchase price variances from budgeted purchase prices on a monthly basis to estimate the impact on product and services to be sold in subsequent stages.

Research and development:

-

- Find cheaper or more suitable input materials.

- Reduce process turnaround time for customer-specific developments as quick responses build customer confidence.

- Regular assessment of project progress with go/no go decision ends stagnant projects earlier and frees up research capacity.

Internal service areas:

-

- Continually re-evaluate out- or insourcing (what do we maintain and repair ourselves, what do we outsource?).

- Outsource maintenance and cleaning and reduce cadence if they are not a prerequisite for operational readiness (make fixed costs more controllable).

- Do not charge fixed costs to recipients in internal activity allocation. The service provider is responsible for its own fixed costs.

Controller:

-

- Fast execution of the planning process and prompt internal reporting are becoming increasingly important because inflation affects the procurement side quicker than the receipt of payments.

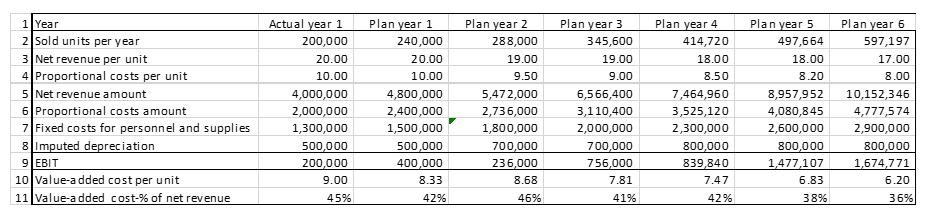

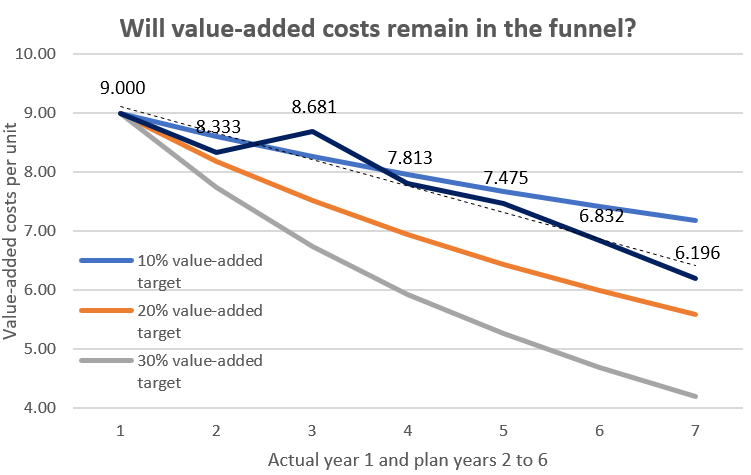

- At low value added, cost management is concentrated on the purchasing side because purchase prices change quickly and strongly. At high value added, the focus is primarily on personnel costs. Inflation tends to lead to job cuts.

- Introduce cost splitting into proportional and fixed costs both in planning and in target to actual comparisons.

- Enable computer simulation of cost and revenue developments so that changes in volumes, prices and costs can be estimated in advance.

- Apply dynamic investment calculations so that the effect of inflation on present values becomes apparent.

Management processes:

-

- Determine responsibilities of individual management positions so that adherence to qualities, quantities, deadlines, and results can be determined.

- Introduce company-wide Management by Objectives and regularly measure and assess the achievement of objectives by individual employees.

- Introduce shop floor data collection also in administrative areas to continuously reduce time consumption in these areas.

Fighting inflation internally is the task of managers at all levels of the hierarchy. If they do not manage to make the total value-added costs grow slower than net revenues, the company will lack the profits to invest in the future and will disappear from the market over time.