It is only in the overall view and in comparison with the plan that the extent to which the BSC proposals have been successfully implemented becomes apparent. To be able to put the overall picture together, quantities, services, times, inventories must be made equal. This can be done in the profitability analysis and in the internal balance sheet.

Contribution Margin Accounting supports BSC

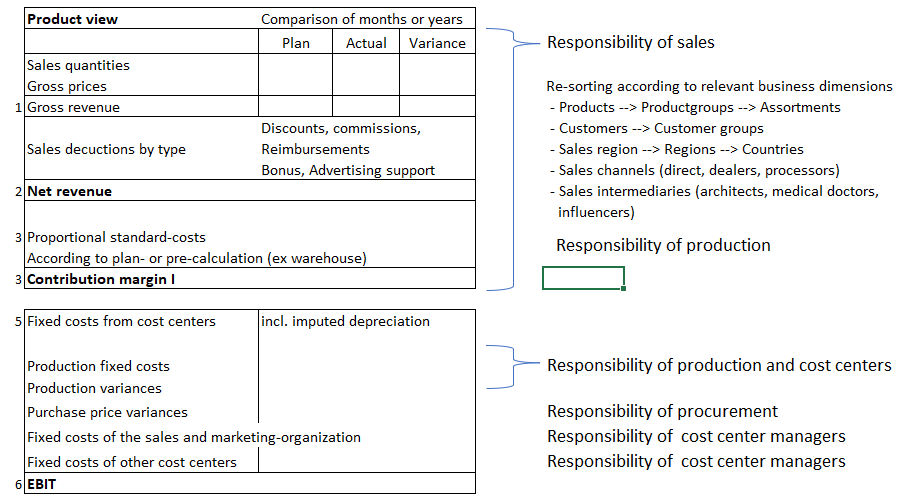

If the profitability analysis is structured as a step-by-step and multidimensional contribution margin accounting, intermediate results can be presented for which the responsible managers can take direct responsibility. In addition, developments over time (from comparisons with the previous month to changes over several years) as well as planned to actual comparisons can be presented. Variances from the plan are shown to the accountable manager. There is no need to allocate variances to product units.

Find an example of stepwise contribution accounting here

Responsibilities and variance analysis

Salespeople can be responsible for net revenue first because they plan and control all the determining variables. If the planned proportional standard production costs are deducted from the realized net revenue of a sale, all variances arising in the downstream functional areas are left out. This allows the selling persons to also take responsibility for the CM I achieved in their area.

In line with the company’s own business model and market development, Contribution Accounting must be structured on a multi-dimensional basis:

-

- In the product group view, the fixed costs of sales promotion can clearly be assigned to the contribution margins of the product groups or assortments. Product group managers can thus take responsibility for the CM I of their product group as well as for their own fixed costs that can be directly influenced. They are thus responsible for the contribution margin of their product group after deduction of their direct fixed costs and their spending variances.

- Analogously, the contribution of a sales territory can also be planned and measured. The CM I achieved in a sales territory (after deduction of the proportional standard manufacturing costs) minus the directly controllable costs of the sales territory (cost center) result in the sales territory contribution.

- If the sales channel is stored in the customer master data for each customer (e.g. direct sales, online, dealer), the contribution margin can also be calculated for this dimension. In this case, the fixed costs of channel support that can be influenced must be deducted from the CM I of the sales channel.

With the outlined multi-level and multi-dimensional CM-calculation, it is possible to clearly assign the achieved CM I as well as the fixed costs and the variances. Those responsible for sales can assess in each case how BSC activities did affect the results of their area.

Variances between the flexible budget and actual costs can occur in all cost centers. The difference between target and actual costs is called spending variance. The respective cost center manager is responsible for them (for the distinction between planned to actual and target to actual see “Flexible budget” in the glossary). The spending variances cannot be allocated to the product units according to their cause. In the stepwise contribution accounting-system they are presented at the lowest summarization level to which there is a clear reference.

Since production needs to adapt to customer demand and at the same time to take into account inventory targets in the warehouse, various types of variances arise for which the production manager is responsible, as he, together with his staff, is to achieve the planned values in the processed production orders. If the lot sizes in production increase due to larger sales quantities, this leads to positive lot size variances, because the setup costs only occur once per production order. If less material is consumed per piece than planned, positive material quantity variances occur. If more good pieces can be produced from the material input than planned, positive yield variances occur. If production orders are processed in cost centers other than those planned (due to bottlenecks), process or routing variances occur. Finally, working time variances occur when more or less time than calculated is used to process a production order in the production cost centers.

All these types of variances must be reported to the production managers, as they are the only ones who can directly ensure that such variances do not occur. Therefore, these variances are not allocated to the units produced and are not reported in the product contribution margins. The variance analysis for the production orders shows by how much the actual costs of the orders produced deviate from the planned costs per unit. Added to this are the spending variances of the production cost centers. Avoiding such variances is the responsibility of the production manager and of his cost center managers.

If differences arise between planned and paid prices in purchasing, purchase price variances occur. For these the purchaser is responsible, not the consuming cost center. Only if the material is purchased directly for a specific production order can a purchase price variance be charged to the order according to its cause. This type of variance arises at the moment of purchase, not at the moment of consumption, see also the post “Standard Cost Calculation of Products“.

These in-depth target to actual comparisons are used for control during the year, so that the responsible persons can quickly determine corrective measures. For the provision of data for the balanced scorecard, the condensed information on services rendered and the recalculated actual costs are usually sufficient.

It follows that the management accounting system, which has been consistently set up in line with decision-making and responsibility, also provides the data required for the implementation of the BSC. Full cost accounting, in which fixed costs are allocated to inventories and from there to the units sold, is not suitable for supplying a BSC. This is because the allocations mean that the people responsible only see to a very limited extent, or not at all, which of their measures had a direct impact on improving process costs.

The combination of stepwise and multidimensional CM- accounting with standard cost accounting with proportional costs leads to clear interfaces between the individual management areas.