Ideas are simple, implementation is everything! This is the mantra of John Doerr, the consultant of Google and other successful companies who introduced the OKR system and sees it as the basis for sensational success in development and results (see: J. Doerr, OKR Objectives & Key Results, 2017).

Ideas are simple, implementation is everything! OKR

In his book, Doerr uses numerous real examples from global corporations as well as small companies to demonstrate that consistent goal orientation is an indispensable key to sustainable success.

The concept of leading with goals is not new. Peter Drucker already laid the foundation for this approach in his publication “The Practice of Management” as early as 1954. George Odiorne described the theoretical concept of Management by Objectives (MBO) and concretized the practical implementation in “The Human Side of Management (1987)”. It seems important to us that Odiorne recognized that the successful application of the MBO system only occurs when objectives are not set by a superior but are transformed into a cross-hierarchical agreement on objectives. Doerr came to the same conclusions (OKR Objectives and Key Results, p. 10).

According to Doerr, an objective determines the “what?”. Objectives should be aggressive and yet realistic, tangible and unmistakable. Their achievement should represent a clear added value for the organization (cf. ibid., p. 226). The SMART formula attributed to P. Drucker (specific, measurable, actively influenceable, realistic and terminated) means almost the same in terms of content.

Key Results express milestones with the associated results. The latter must be measurable, be it with key figures or with documented results (OKR, p. 226).

Management by agreeing on objectives has been an integral part of our management control systematics for years. We are therefore very pleased that Doerr, with his examples from the practice of successful companies, brings two elements to the fore: The objectives must be agreed upon so that the results to be achieved by the individual actors fit in with the overall objectives of the organization and each objective must be defined in a measurable or at least verifiable form. Every manager will confirm from his experience that finding objectives is relatively easy, but realizing them is very exhausting.

In our opinion, objectives, their metrics and the results achieved should be documented in the management control system. Google even goes so far as to allow every employee to see all objectives, including those of his colleagues, bosses and even the executives.

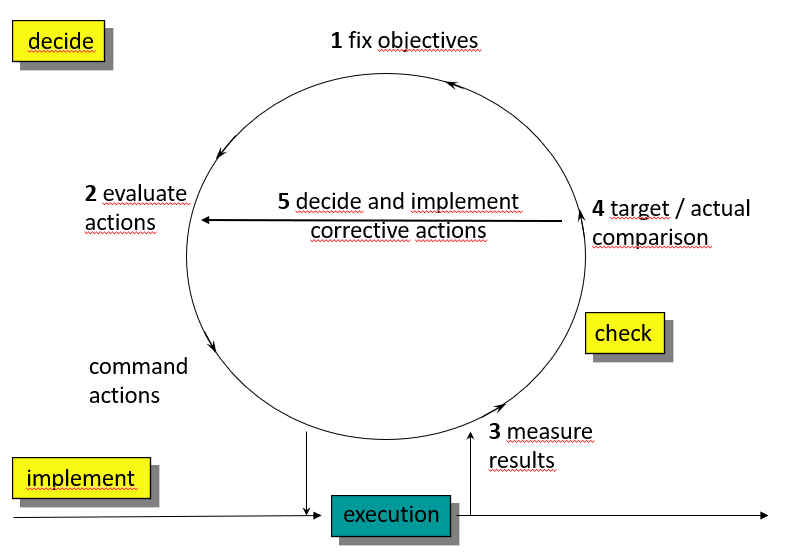

Management by agreeing on objectives is completely interwoven with the management cycle in the integrated management system, since the latter also serves to determine the results and to look for corrective measures if a goal has not been fully achieved. In the various planning or management levels (corporate policy, strategy, operational management) it is also necessary to agree on objectives, to provide the necessary resources and, in accordance with the management cycle, to analyze whether the intentions have become results.

These interrelationships are consequently also determinants for the design of the management control system.