When actual data is available to measure realized cost reductions, it is too late! In the meantime, the competition has already acted, which may have resulted in shifts in market share that give faster growing companies better opportunities for cost reductions than to one’s own company. Consequently, cost reduction potentials must be actively sought, planned and implemented.

Improving the cost position requires creative, innovative ideas. Realizing cost reductions means strenuous operational work.

Localize Cost Reduction Potentials

It is important to remember that effectiveness (scope and impact) comes before efficiency (less input for more output).

Giving regular feedback to one’s own employees on the performance and quality achieved increases effectiveness because the people being managed can thus control and improve their own efforts (see the post “Master Plan for Integrated Planning and Control”).

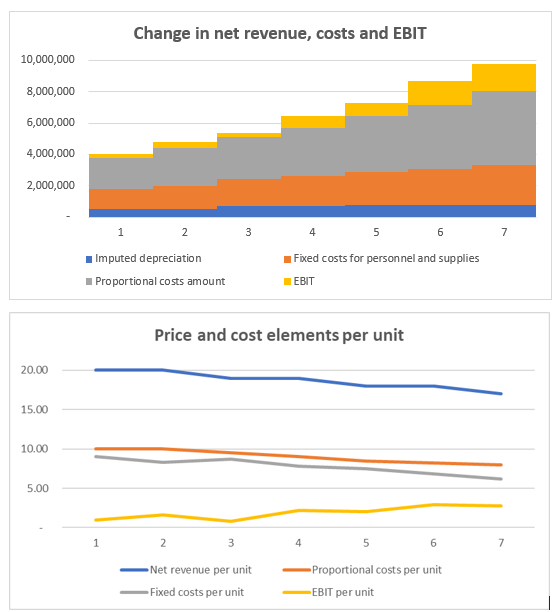

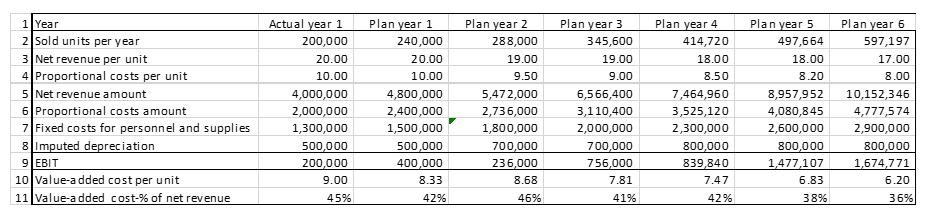

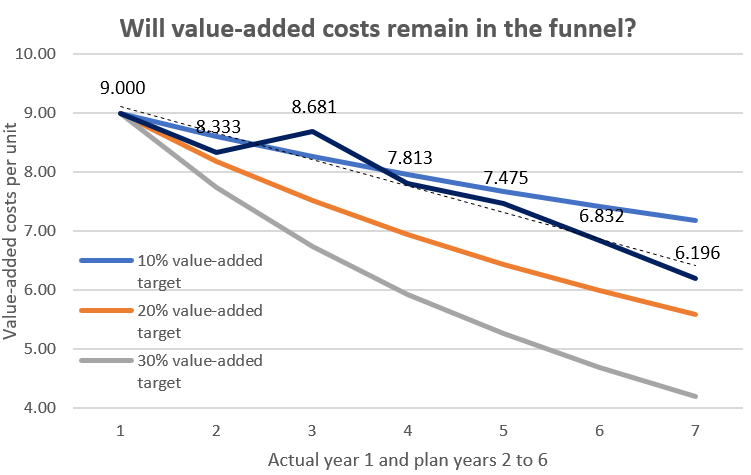

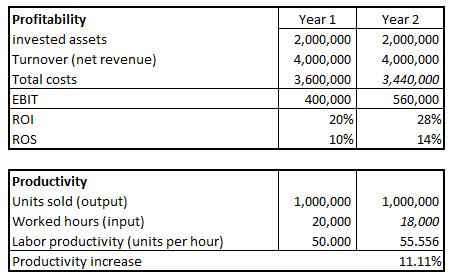

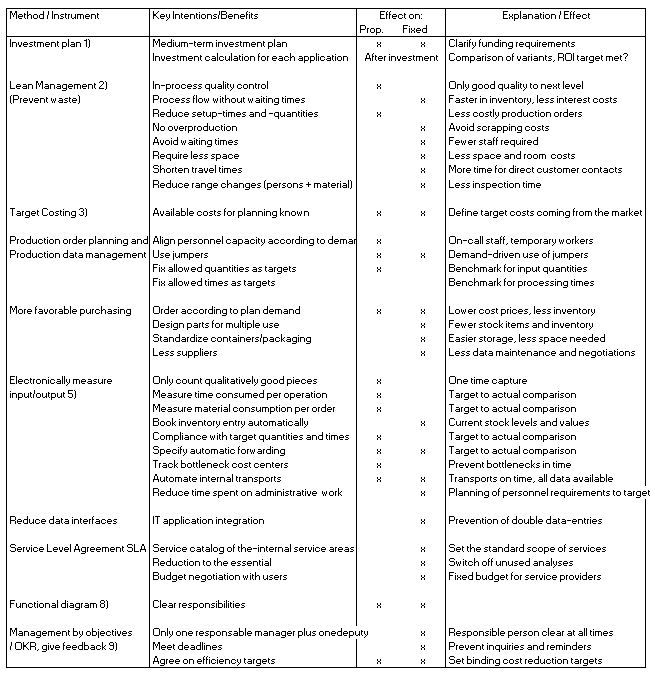

In order to be able to localize and realize cost reduction potentials, many methods and procedures have already been developed and recommended. The intention is to reduce costs or to let them grow slower than the realized net revenues, thus generating profits that can be used for the expansion of the organization.

Some proven successful methods and tools are listed below together with the improvements hoped for by their application.

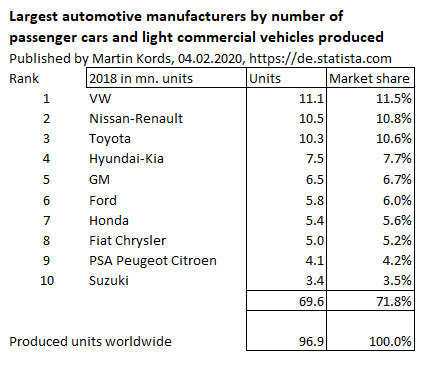

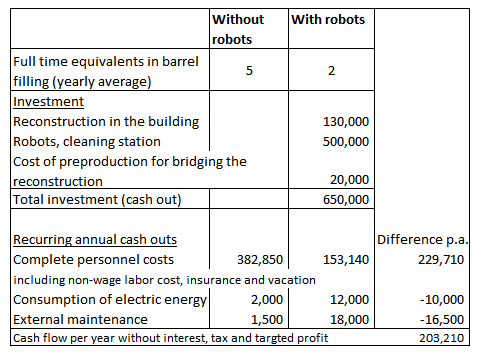

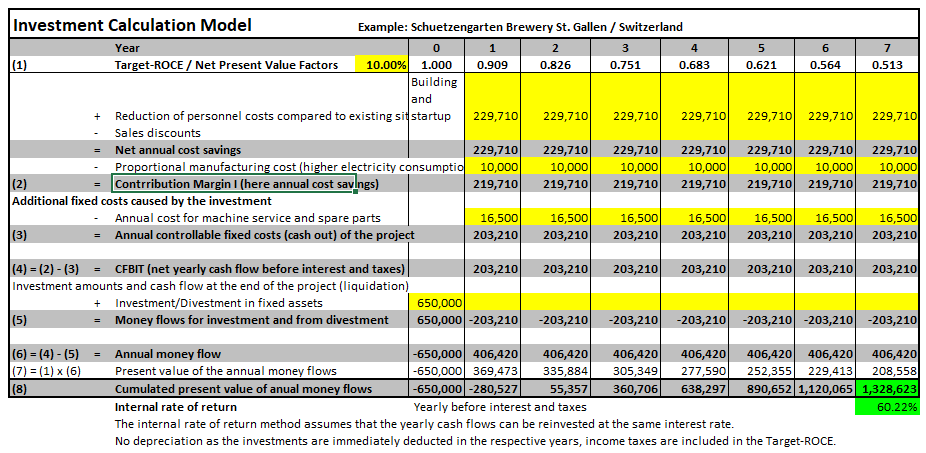

1 Strategy and investment planning see the capital budgeting Excel-download

3 Target costing: In simplified terms, target costing is intended to bring the expected future market into product development and production, thereby piloting a strong cost position as early as in the product design stage. A target cost calculation is used to determine the maximum costs that can be incurred for manufacturing the product, based on the net revenue that can be achieved on the market. The current percentages for the share of administrative and sales costs and for the target profit are deducted from the net revenue (estimation of a target contribution margin for these functions). The amount available for producing the planned quantities remains as the residual. For the quantification of the various items, dynamic investment appraisal must again be used, since target costing decisions usually require investments to be taken into account and implementation often takes several years.

5 Measure input/output electronically

6 Plan and record internal tasks

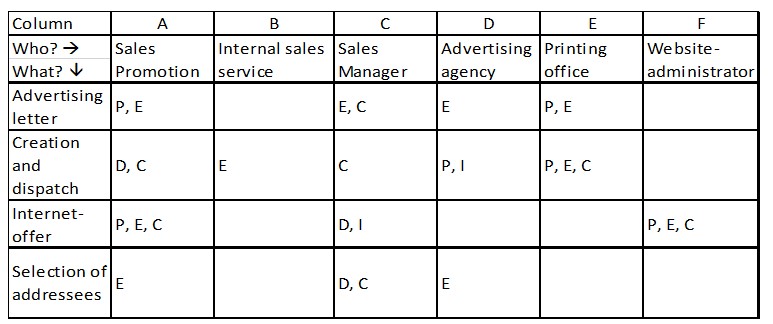

7 Service Level Agreements (SLA) This is a service agreement between clients (internal divisions, functions and cost centers) and performing cost centers for the regulation of recurring services. An SLA is often also agreed with external service providers (e.g., IT outsourcing).

The purpose of such a service agreement is to describe the services to be provided by the service provider as completely as possible for the contractual partners. Care must be taken to ensure that the services are defined in such a way that they can be measured or at least verified.

In the SLA, the contractor is one or more cost centers; the customer is the community of cost centers receiving the services.

The supplier (cost center manager) is responsible for the service provision and for the target cost compliance. Therefore, he also has the obligation to say no if (in the plan or in the actual) more than what has been agreed is demanded. In return, the clients are responsible for approving the budget for the specified services. If they want more service or to pay less, the service providers can reject the proposed conditions. This agreement work must be fixed as part of the budgeting process. After all, once the authorizations are in place, the staff is hired and the money is spent.

Services provided by internal functions are often very diverse and can only be predicted imprecisely. This makes it difficult to agree on an SLA. Nevertheless, it is worthwhile for both contracting parties to describe the work to be performed as completely and comprehensibly as possible. After all, these minutes are an important element for budgeting and comparing planned/actual data. The following should be specified for each item

-

- Quantity: e.g., preparation of a monthly financial statement or ensuring 99% availability of applications.

- Quality: e.g., according to the principles of proper accounting or the response times of the systems to be maintained.

- Deadlines: e.g., on the 5th working day of the following month or response time until faults are resolved (service level).

- Costs / results: budget compliance.

The tasks to be performed in an SLA should be limited to what is necessary. As a result, the cost of SLA fulfillment should increase more slowly than the CM-volume of the company.

When an SLA is released, contractors may deploy their personnel and resources. The internal customers must periodically be given the opportunity to comment on the extent and quality of service delivery.

SLA costs are fixed costs. They are incurred for the using cost centers, not directly for the products. Due to the lack of a direct cause-effect relationship, they cannot be allocated to the products.

Operational Excellence

Many brilliant strategic decisions have laid the foundation for exponential development of companies. Again, many of these companies have found their way into economic history as “success stories”. They are quoted in books and in seminars.

However, in the cases known to us, the fact that things got this far was always due to “operational excellence”. In our view, fine-tuning details, mastering processes, distinguishing between what is necessary and what is “good to have”, and continuously improving implementation are basic elements of successful corporate management, both in the area of sales and distribution and in the persistent improvement of the company’s own cost position.